This article is an introduction to understanding Intel’s assembly language while debugging a computer program.

Debugging in assembly can be a daunting task and not every developer likes to make sense of the mnemonics that appear on the screen. While debugging, one is normally used to viewing local variables, parameters and syntax highlighted code in the most user friendly manner and that is the primary reason why many developers dislike debugging in assembly initially.

Why Debug In Assembly?

1. You have a binary and its corresponding code but the build environment is not functional. This could be because of missing tools, unavailable compilers and the lack of understanding of complex scripts and steps needed to recreate the binary.

2. You are dealing with a release build only bug and the debug symbols are unavailable or you are dealing with a third party library and don’t have access to the source code.

3. You like to have fun.

What You Need?

1. A debugger that can display assembly language (Visual Studio, WinDbg, gdb, XCode are capable debuggers).

2. A ready reference to the Intel instruction set. Google works just fine.

3. Patience and maybe a link to this article. 🙂

The key to understanding debugging in assembly is to understand how functions are called, parameters are passed, local variables accessed. The rest can be understood by referring the Intel Instruction set while debugging the assembly code.

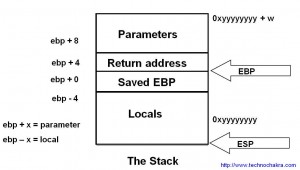

The diagram below is roughly how a stack should look like once a function call has been made. When one encounters assembly, mapping the code to this diagram should simply the debugging experience. Note that the stack grows downwards.

Passing Parameters To A Function

Parameters are the first to be pushed onto the stack. The caller of the function pushes them from right to left.

Cleanup Of Parameters

Parameter cleanup may happen in the function that was called (e.g. stdcall calling convention) or by the caller of the function (e.g. cdecl). Various kinds of calling conventions of the x86 architecture are explained in detailed in this wiki article. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X86_calling_conventions Looking right after the function call gives a good idea of what convention was being used when compiling the code.

Take note that if cleanup happens in the function being called, variable number of arguments cannot be passed to it. Whereas it becomes possible to do this if the parameter cleanup happens outside the function. This essentially is the main difference between stdcall and cdelc calling conventions on a x86 architecture.

The Function Call

Before control is passed to the function, the return address where the program is supposed to resume once the function has finished execution is pushed to the stack.

To recap, parameters are pushed first, followed by the return address. Later depending on the calling convention of the function, you may see cleanup hhappening right after the function call or within the function itself.

In the diagram above, as the stack grows downwards, the parameters are at the top followed by the return address.

Example

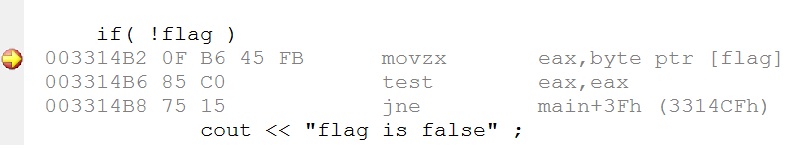

Take a look at the snippet and the equivalent assembly below :

The Function

The function usually starts with a prolog and ends with an epilog

The prolog is either a simple ENTER instruction or more commonly, it saves the ebp register and copies the stack pointer value in it so as to use it as frame pointer.

push ebp

mov ebp,esp

The epilog just reverses what the prolog had done. It is implented by a LEAVE instruction or is implemented as follows

mov esp,ebp

pop ebp

The ret instruction returns from the function to the return address stored in the stack.

A compiler switch allows one to omit the frame pointer (fpo – frame pointer omission) which effectively removes the prolog and epilog and uses the ebp register for other optimizations. It is easy to demarcate function boundaries where the frame pointer is not omitted but one should be aware of the absense of these entry and exit points.

Allocation Of Local Variables

Local variables are allocated on the stack. The total size of the local variables is computed at compile time and at runtime those many bytes are reserved on the stack.

004113A0 push ebp

004113A1 mov ebp,esp

004113A3 sub esp,0E8h

Note that in the example above, 232 (0xE8) bytes are being reserved for local variables.

The above code will also help in understanding why local variable allocation is much faster than requesting memory from heap.

Local Variables And Parameters In Assembly

The most important part in assembly is to be able to identify access to locals and parameters. The frame pointer that is set in the prolog, acts as the reference pointer using which all variables can be accessed. If you add to the frame pointer (Remember : P for Plus and P for Parameters), you will access parameters. If you subtract from the frame pointer, you will be able to access local variables.

mov byte ptr [ebp-20h],3

mov byte ptr [ebp+20h],5

The first line above access a local variable whereas the second accesses a parameter.

In the case of frame pointer omission, everything is calculated with respect to the stack pointer. Therefore [esp + 20h] might refer to a local or a parameter depending on where the stack pointer currently points to. And if say a register is pushed on the stack, the same variable will now be referred using [esp + 24h]. Debugging functions that have optimized out the frame pointer is not that easy as the changes made to the stack pointer need to be constantly tracked.

This article is an introduction to understanding Intel’s assembly language while debugging a computer program.

Debugging in assembly can be a daunting task and not every developer likes to make sense of the mnemonics that appear on the screen.

While debugging, one is normally used to viewing local variables, parameters and syntax highlighted code in the most user friendly manner. This is the primary reason why many developers dislike debugging in assembly initially.

Why Debug In Assembly?

Debugging in assembly is not an optional skill to have. Every developer encounters a situation where there is no other alternative other than cracking open the assembly code. Here are a few reasons why a developer should get their hands dirty with this skill –

- You have a binary and its corresponding code but the build environment is not functional. This could be because of missing tools, unavailable compilers or the lack of understanding of complex scripts and steps needed to recreate the binary.

- You are dealing with a release build only bug and the debug symbols are unavailable or you are dealing with a third party library and don’t have access to its source code.

- You like to have fun 🙂

What You Need?

- A debugger that can display assembly language (Visual Studio, WinDbg, gdb, XCode are capable debuggers).

- A ready reference to the Intel instruction set. Google works just fine.

- Patience and maybe a link to this article. 🙂

The key to debugging in assembly is to understand how functions are called, parameters are passed, local variables accessed. The code flow and logic can be understood by looking up the Intel instruction set .

The diagram below (click for larger image) is roughly how a stack should look like when a function is called. Mapping the assembly code to this diagram should simplify the debugging experience. Note that the stack grows from top to bottom.

Passing Parameters To A Function

Parameters are the first to be pushed onto the stack. The caller of the function pushes them from right to left.

Cleanup Of Parameters

Parameter cleanup may happen in the function that was called (e.g. stdcall calling convention) or by the caller of the function (e.g. cdecl). Various kinds of calling conventions of the x86 architecture are explained in detail in this wiki article. Stack cleanup code right after the function call gives a good idea of the calling convention being used.

Take note that if cleanup happens in the function being called, variable number of arguments cannot be passed to it. In contrast, variable number of arguments can be implemented if the parameter cleanup happens outside the function. This essentially is the main difference between stdcall and cdelc calling conventions on a x86 architecture.

The Function Call

Before control is passed to the function, the return address (where the caller is supposed to resume after the function completes execution) is pushed on the stack.

To recap, parameters are pushed first, followed by the return address. Later depending on the calling convention of the function, you may see cleanup happening right after the function call or within the function itself.

In the stack diagram above, as the stack grows downwards, the parameters are at the top followed by the return address.

Example

Take a look at the snippet and the equivalent assembly below :

[1]int a = 4;

[2]mov dword ptr [a],4

[3]

[4]char c = 0;

[5]mov byte ptr ,0

[6]

[7]c = f(a, 22);

[8]push 16h

[9] mov eax,dword ptr [a]

[10] push eax

[11]call f (4111D1h)

[12]add esp,8

[13]mov byte ptr ,al

- In line [8], the constant value 22 (16 hex) is being pushed on the stack.

- In line [9-10] the variable ‘a’ is pushed.

- Line [11] is the function call to f() which implicitly pushes the return address.

- The return value of the function is passed in a register and copied in variable ‘c’ (line[13]).

- In line [12] one can see that 8 bytes are being discarded from the stack as f() uses the cdecl calling convention and cleanup needs to happen in the caller function.

The Function

The function usually starts with a prolog and ends with an epilog.

The prolog is either a simple ENTER instruction or more commonly, it saves the ebp register and copies the stack pointer value in it so as to use it as frame pointer.

push ebp

mov ebp,esp

The epilog just reverses what the prolog had done. It is implented by a LEAVE instruction or is implemented as follows

mov esp,ebp

pop ebp

The ret instruction passes control from the function to the return address stored in the stack.

Compilers provide a switch that allows one to omit the frame pointer (fpo or frame pointer omission) which effectively removes the prolog and epilog and uses the ebp register for other optimizations. It is easy to demarcate function boundaries where the frame pointer is present but one should be aware that the entry and exit points may be absent.

Allocation Of Local Variables

Local variables are allocated on the stack. The total size of the local variables is computed at compile time and at runtime those many bytes are reserved on the stack.

004113A0 push ebp

004113A1 mov ebp,esp

004113A3 sub esp,0E8h

Note that in the example above, 232 (0xE8) bytes are being reserved for local variables.

The above code will also help in understanding why local variable allocation is much faster than requesting memory from heap. Allocating local variables requires moving the stack pointer whereas memory heap management is much more complex.

As the return address and local variable area are very close to each other, buffer overflows can be caused if data is written past the the local variable area which can then overwrite the the return address. When this return address if forced to point to shell code (or to some other code placed intentionally by a hacker), such a buffer overflow is termed as an exploit.

Local Variables And Parameters In Assembly

The most important part in assembly is to be able to identify access to locals and parameters. The frame pointer that is set in the prolog, acts as the reference pointer using which all variables can be accessed. If you add to the frame pointer (Remember : P for Plus and P for Parameters), you will be able to access parameters. If you subtract from the frame pointer, you will be able to access local variables.

mov byte ptr [ebp-20h],3

mov byte ptr [ebp+20h],5

The first line above accesses a local variable whereas the second accesses a parameter.

In the case of frame pointer omission, everything is calculated with respect to the stack pointer. Therefore [esp + 20h] might refer to a local or a parameter depending on where the stack pointer currently points to. And if say a register is pushed on the stack, the same variable will now be referred using [esp + 24h]. Debugging functions that have optimized out the frame pointer is not that easy as the changes made to the stack pointer need to be constantly tracked.

Conclusion

Debugging in assembly is not only fun but a useful tool to debug difficult problems. Different debuggers provide different interfaces to interact with the assembly code but under the hood, all programs work alike. Understanding this is the key to debugging in assembly with ease.